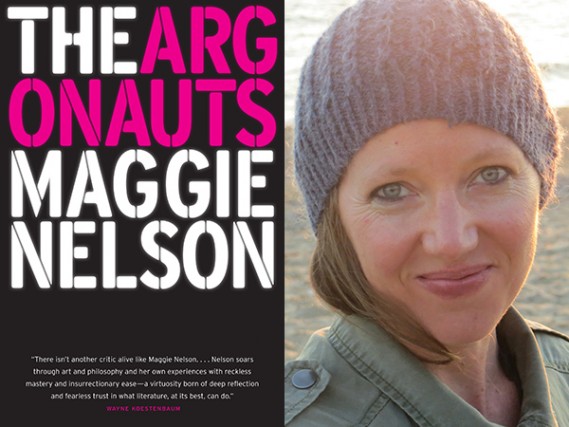

Maggie Nelson Looks at Love, Gender and Family-Making in “The Argonauts”

Maggie Nelson (2013 Literature) has made a name for herself as a border-smashing writer of books that straddle poetry and prose, academic writing and cultural reporting, memoir and criticism. Today, Nelson’s Creative Capital-supported project, The Argonauts, is published in wide release by Graywolf Press.

The Argonauts centers on a romance: the story of the author’s relationship with artist Harry Dodge, who is fluidly gendered. Nelson describes the complexities and joys of becoming a stepmother to Harry’s son, as well as her journey to conceive the child who they are now raising together. Writing in the spirit of critics like Susan Sontag and Roland Barthes, Nelson’s experience serves as a way to explore how iconic thinkers and theorists have tried to untie the vexing knots that limit the way we talk about gender and the domestic institutions of marriage and childbirth. I spoke with Maggie to learn more about the development of The Argonauts.

Jenny Gill: I’m curious how your writing timeline overlapped with and unfolded alongside the life events you write about in the book. When did you start writing The Argonauts, and how did the book and your life change or evolve over that period?

Maggie Nelson: I didn’t set out to write The Argonauts as a book. In late 2010 I wrote a long piece on Eve Sedgwick, which I gave as a talk at CUNY in March 2011, then in early 2012 I wrote a long review of Sedgwick’s posthumous book, The Weather in Proust, for the LA Review of Books. Then my son was born. Later that year I wrote an essay for artist A. L. Steiner’s November 2012 show “Puppies and Babies,” in which I developed some ideas about “sodomitical maternity,” a great phrase set forth by critic Susan Fraiman. All of these pieces were basically me challenging myself to say “yes” to occasional writing, since I usually say “no” (I can be kind of mono-focused on book writing, at the expense of smaller outings). During all this time, I was also writing more diaristically, about my son, my relationship, my thoughts about family, politics, queerness, sex, gender and so on. It wasn’t until fall 2012 when I looked at a lot of this work and thought, maybe this could or should all go together. At which point I started fashioning it into a long essay of sorts.

Once I smelled the book in it, as it were, I got to work. I didn’t know how long it would be, at first—it started out feeling slight, but once the 50,000 word mark came into sight, that seemed respectable enough for a book. I basically wrote the book in 3 hour stretches on the 2 days a week when I had a babysitter and didn’t have to be teaching, over the first two years of my son’s life. A lot changed over that time—first I was writing when pregnant, then I was writing about my son as a baby as he was speeding out of infancy, then, in the final endgame, I was looking back on the whole time. Eventually it seemed like it made sense to begin the story when I met my partner Harry, which was in the fall of 2007, and end it wherever it ended—though with writing like this, the end is always somewhat artificial, since life goes on.

Jenny: Like many of your other books, The Argonauts is sort of a hybrid non-fiction work, melding autobiography and theoretical inquiry. Which writers/thinkers did you draw on most heavily?

Maggie: D. W. Winnicott was the primary muse. And Roland Barthes, from whence the title derives. But there were, are, many others, too, many of whom are explicitly discussed in the book’s pages; others I flash by pretty quickly, but they remain deep within me: Peter Sloterdijk, Fred Moten, Susan Fraiman, Sara Ahmed, George and Mary Oppen, Cathy Opie, Lucille Clifton, Allen Ginsberg, Dana Ward . . . the list could go on and on.

Jenny: What have you learned from your relationship with Harry that you wish people who haven’t had any direct experience with gender fluidity could learn? Are there better ways that we as a society could or should talk about or understand gender identities and unconventional families? (This is a BIG question, I know!)

Maggie: It IS a big one, and I’m afraid I’m going to have to punt it, for the most part. I will say that I don’t really like the bifurcation of families into “normal” vs. “unconventional,” nor do I really love “family” as a primary unit to talk about people’s wildly disparate ways of making kinship and community. In my experience, when you scratch the surface of a so-called “normal family,” in just about every case I can think of, there are “unconventional” lines of kinship, be they of a happy or unhappy variety. So I guess I think it’s important not to presume to know how any group of people has come to call itself a family, and to refrain from freely indulging in normalizing, disciplinary uses of gender and sexuality (and race) when you really don’t know what’s going on.

All of which is to say: while our sets of presumptions may feel to us quite natural or blameless, it’s good to recognize that they can often have a disciplinary effect on the person you’re talking to. So, you know, before you dive in with your “can I get you something to drink ladies?,” consider backing off a little, giving people and their gender(s) some space. Don’t force people into identifications that are in fact corrections; the history of such corrections is a bloody one.

Jenny: That’s a great answer—thank you for that. And a related question, do you hope readers might think differently about childbirth and motherhood after reading your book?

Maggie: I don’t have an agenda here, save the old “pluralize and specify” approach. A student recently told me that she was told in a writing workshop that childbirth narratives were kind of hashed, and I was dumbstruck, as I think I’ve read but two nonfiction literary narratives of childbirth written by women in my whole life, and I get around. So I’m glad to contribute to what seems to me a somewhat meager canon. I guess I might also say that it’d be cool if people stopped opposing motherhood and having a brain, but if they’re still doing that, I feel like that’s their problem, not mine.

Jenny: How did you settle on the title, The Argonauts?

Maggie: Well, as always, there were other titles in the mix, but I wanted to pay homage in some big way to Roland Barthes, as his writing, specifically Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes, has been so important to me, and was so important to me here. And I wanted to call attention to the “I love you” aspect of the phrase (you have to read the original Barthes to know what I’m talking about—sorry!—but it’s also explained not so far into the book!). Lastly, I liked the idea of the title invoking a tribe of people and their actual bodies in plural, and “The Argonauts” does that (references to Greek mythology need not apply).

The Argonauts is published by Graywolf Press. Order your copy online through Graywolf or Amazon or ask for it at your local bookstore.