Jeffery Allen Releases "Song of the Shank," a Lyrical Work of Historical Fiction Both "Dream-like and Real"

Jeffery Renard Allen’s Creative Capital-supported project, the novel Song of the Shank, is being published by Graywolf Press on June 17. At the heart of this remarkable work is Thomas Greene Wiggins, a 19th-century slave and improbable musical genius who performed under the name Blind Tom. As the novel ranges from Tom’s boyhood as a sightless, probably autistic piano virtuoso to the heights of his performing career, the inscrutable savant is buffeted by opportunistic teachers and crooked managers, crackpot healers and militant prophets. In his symphonic novel, Allen blends history and fantastical invention to bring to life a radical cipher, a man who profoundly changes all who encounter him.

Song of the Shank is already garnering tremendous critical acclaim, including a forthcoming review on the front cover of the New York Times Book Review that calls the novel “masterly” and praises Allen as “a prodigiously gifted risk-taker.“ In the Atlanta Journal Constitution, Jeff Calder calls Song of the Shank “a landmark of modern African-American literature,” and concludes, “Reading through this sagacious volume is like stumbling on a crooked monument covered in celestial carvings, something that aims for the stars and ends up reconfiguring constellations.” In a starred review, Kirkus Reviews raves, “If there’s any justice, Allen’s visionary work, as startlingly inventive as one of his subject’s performances, should propel him to the front rank of American novelists.”

I connected with Jeffery to learn more about this extraordinary literary achievement, a lyrical, ambitious and historically significant novel ten years in the making.

Jenny Gill: Thomas Greene Wiggins is a fascinating historical figure. When did you start conceptualizing a narrative around his life and experience?

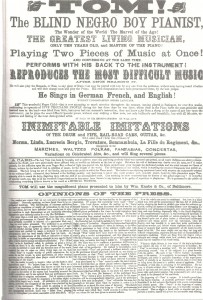

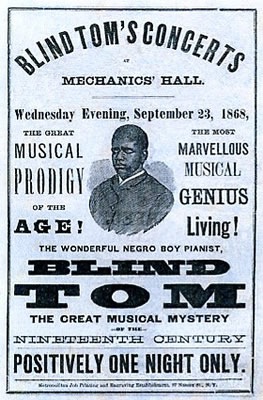

Jeffery Renard Allen: I first became interested in writing a fictional narrative about Tom Wiggins in 1998 after reading a brief account of his life in Oliver Sacks’ book An Anthropologist on Mars. Here was a guy who was one of the most famous people of his time, probably the most famous pianist of the 19th century, the first African American to perform at the White House, who had somehow slipped through the cracks of history. I was also intrigued by Sacks’ description of Tom’s stage performances, which were ahead of their time in his ability to play three songs at once in different keys and play compositions that mimicked non-musical phenomena.

As memory serves me, I didn’t first write any pages about Tom until the fall 2001 when I was a fellow at The Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library. At that stage in the writing I was stuck on a bone-head idea of writing a massive novel that would have four independent story lines set at different times and places, and I thought about Tom as one narrative of the four. A fellow writer at the center, the novelist Carmen Boullosa, suggested that I should “cut the pretension,” as she put it, and focus on Blind Tom. However, it took me another two years or so to acknowledge her sage advice.

VIDEO: Compostions by Blind Tom, played by John Davis

From 2003 on, Blind Tom became both the focus of this novel and the focus of all my writing activities, a way of saying that it took me about ten years to write the novel, which I worked on from 2003 until the spring of 2013. I started to see how Tom’s story involved subjects of tremendous interest to me—music, creativity, performance, family, bondage and freedom—as well as certain subjects that I found intriguing and wanted to learn more about—blindness, autism, savants, piano music—all fertile spaces for a novelistic imagination.

Jenny: How would you describe the narrative voice or tone that you use in the novel?

Jeff: I suppose my fiction is known for what many have called its lyrical or poetic prose, and Song of the Shank is no exception to that. At the same time, in this novel I tried to construct a range of lyrical voices, with passages in the book that some might call meta-fictional narration, others that seem to echo the 19th-century prose style of someone like Dickens or Dostoevsky, and scenes and sections that use other voicings (a musical term for the different ways a musician plays the notes that form a single chord). Put simply, I play with voice and tone since I thought the book should have the type of musical expansiveness that in my imagination characterizes Blind Tom.

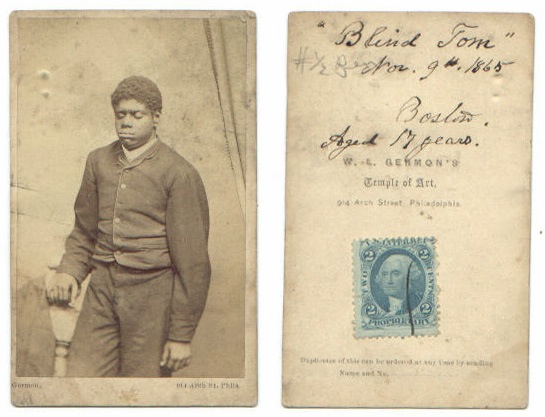

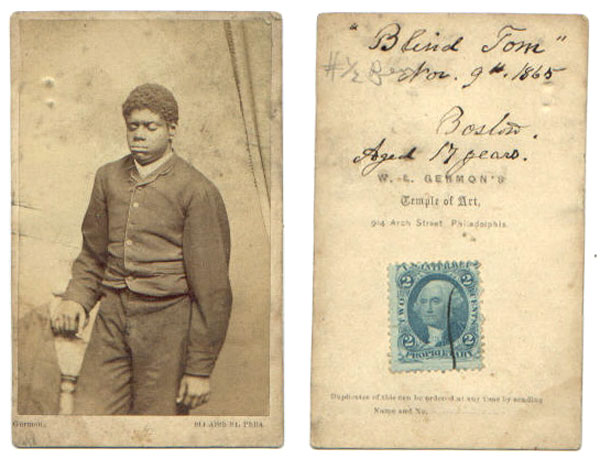

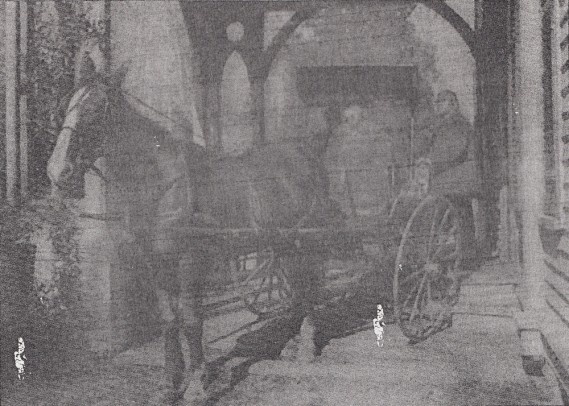

A grainy 19th-century photo of Tom Wiggins. Allen noted, “We had no luck tracking down the original to get a higher resolution image, but I always found it perfect for the novel as is—representative of the shadowy Tom.”

That said, I would also emphasize that the novel has cohesion and is more than simply an “exercise in style” (a la the celebrated Raymond Queneau novel). So while the tone may vary—at times dark and meditative, at times humorous—I want the book to feel both concrete and mysterious, dreamlike and real, historical and fantastic, haunting and tragic, and both angry (yes) and celebratory. The prose is almost always highly interior, to put you inside the characters, and the dialogue in the novel serves to do that too, even when Tom makes certain cryptic statements.

And it was also important to me for the novel to be highly allusive and referential. The careful reader will see that Tom contains the entire sea of African time inside him, all of human history, past and future.

Jenny: You received the Creative Capital award for Song of the Shank in the very first year of our Literature awards program—2006. Over the years, we’ve learned that, aside from the award money, one of the most important things we can give to our artists is time. Meaning that we have an open timeframe for working artists and projects, and that we encourage artists to take the time that they need. You’ve been working on this book for many, many years, and I’m curious to hear what happened during that time, and how the project evolved.

Jeff: Let me get personal for this one. It took me a year of stumbling (from 2003 to 2004) to simply figure out how I could put my stamp on Tom’s story. So I wrote and wrote for the next four years then entered a hospital the emergency room on Christmas Day in 2008, deathly ill with complications from malaria that I had unknowingly contracted in West Africa the previous summer. I was in pretty bad shape, and for a time it looked as if I would die and never have the opportunity to finish the novel. So I spent some six weeks in the hospital, including about two weeks in intensive care, and when I was finally released, I started writing like a fiend, hellbent on finishing the novel. I did so in about three months, then submitted it to my editor.

The challenge from then on was one of learning to heed the sagacious advice of my editors at Graywolf, Ethan Nosowsky and Fiona McCrae, and have another go at the book with their suggestions in mind, of committing to a slow process where I was willing to do the things I needed to do to make the book work. In terms of the actual revising, part of that process involved simply fleshing out certain sections and scenes, and cutting certain others, and figuring out the best way to structure the novel. However, I also arrived at a crucial conceptual idea that helped bring everything else into focus. I realized that I needed to make selective use of actual images—photographs, drawings, newspaper clippings, etc.—in the novel. (The novel has about twenty images in all.) Then too, not surprisingly a near-miss of the grave gives you a perspective on life that you wouldn’t otherwise have. My last five years of work reflect that hard-earned perspective, every word on every page.

Jenny: Was there anything in particular about Creative Capital’s support (the financial support and/or advisory services) that impacted the project?

Jeff: Kudos, Creative Capital has been great to me. To mention a few things of many, the financial support gave me the funds I needed to purchase a new computer (desktop) and a laptop that I could use for travel, money to create my website, and funds to purchase research materials (books, CDs, and DVDs). I was also provided with funds that allowed me to travel and write. Importantly, in the summer of 2007 I spent an extended amount of time on the island of Lamu off the Kenyan coast. Lamu (and later Zanzibar) became crucial in shaping the fictional island of Edgemere in my novel, one of the book’s principal locations.

Even more, through Creative Capital I found a publisher. When I met Ethan and Fiona through Creative Capital, I had no idea that I would go on to work with them at Graywolf Press. Fiona was one of the professional advisors that Ethan, in his role as Creative Capital’s Literature Program Consultant, brought to the Creative Capital Artist Retreat in 2006. At the Retreat she agreed to read a story collection that was having a hard time finding a home, and she would go on to publish that book (Holding Pattern) in 2008. And now of course they have published Song of the Shank, a beautiful production. I should also note that the other advisors Ethan brought to the Retreat also gave me valuable suggestions, largely about how to promote the novel once it was done and out into the world, the stage where I am now with the novel.

Jenny: What other projects do you have in the works?

Jeff: Right now I am working on some short stories under the working title Radar Country. I’m thinking that my next book will be a collection of stories (and possibly novellas) divided into four sections after Coltrane’s seminal album “A Love Surpreme.” And another novel is also on the horizon. For some time now I have been mulling over a novel of speculative fiction. Such would give an interesting shape to my novelistic production, since Rails Under My Back was a novel focused on contemporary America (the 1980s and 1990s in the black neighborhoods of cities like Chicago, where I grew up), Song of the Shank is historical (a slanted history, my riff on America in the mid-19th century), and this speculative novel would be set in the future. It seems to take me ten years to write a novel. So I need to recharge my batteries before I dive into that one. Wish me luck.

“Song of the Shank” will be published by Graywolf Press on June 17, 2014. Order it online from GraywolfPress.org or Amazon.com.