Artist to Artist: Lisa Bielawa and Arturo Vidich Talk Performance in the Unlikely Spaces of Abandoned Airfields

Lisa Bielawa will stage a musical performance at Berlin’s Tempelhof Field May 10-12.

Artists Lisa Bielawa (2006 Performing Arts) and Arturo Vidich (2013 Performing Arts) have more in common than meets the eye. Though they work in different media—Bielawa is a musician and composer, Vidich is a choreographer—both Creative Capital grantees are taking on community-building and place-making in an unusual space: the repurposed military airfield.

Bielawa’s Airfield Broadcasts project has two iterations, one at the Tempelhof Field in Berlin (premiering this weekend, May 10-12) and the other at Crissy Field in her native San Francisco (October 26-27). Each performance involves between 100 and 1,000 musicians, from student groups to professional orchestras, performing Bielawa’s hour-long composition in these massive public spaces for audiences both intentional and accidental. Bielawa incorporates musical composition and choreography to fully explore the sonic and spatial relations of each former airfield.

An improviser with a dance degree from Wesleyan and a pilot’s license, Vidich is embarking on an ambitious new work supported by Creative Capital. You Are It is an interactive performance for 3,000 people (playing Tag) and a “human-powered-hybrid-electric” airplane, made and manned by Vidich and collaborator Daniel Wendlek. The plane videotapes the Tag game from the air, and Vidich is proposing to present the footage as in-flight entertainment on commercial jets. You Are It is a one-day event, taking place at Floyd Bennett Field in Southeast Brooklyn.

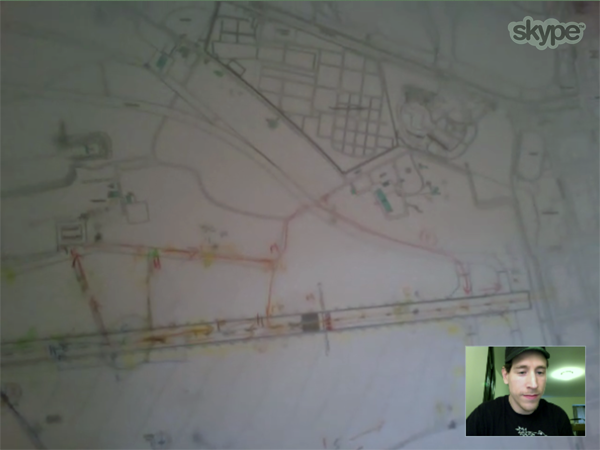

We set Lisa and Arturo up on a Skype date to discuss the possibilities and challenges of their projects, and their experiences with these three former airfields.

Lisa Bielawa: It’s nice to meet you!

Arturo Vidich: Nice to meet you, too. Digitally. Handshake. So, you’re in Berlin right now?

Lisa: I’m in Berlin, yeah, and it’s raining right now, but I can show you something just to get us started. I’m going to show you what I’m working with, which is this map of Tempelhof Field. Do you see that blue is the Terminal Building. The largest standing piece of fascist architecture still in existence. And then I don’t know if you can see all the colored pencil marks on the runways and stuff.

Arturo: Yeah, I do.

Lisa: Each color is a group of between 20 and 50 musicians. And I’m figuring out where they’re all going to walk at which points in this piece. I’m doing music stuff, finishing up the music composition, but I also have to go and walk around to make sure that I’ve left them enough time in the composition so that they can get wherever they need to go. It’s been almost three years that I’ve been working on this.

Arturo: Wow.

Lisa: One of the things that people often ask me is, because I’m a composer, is this about community? Did you go after you had this idea of doing a piece with hundreds of musicians, did you go out and scout locations? And it was actually the opposite way because Tempelhof, I’m sure you know because you’re, like, the airport guy…

Arturo: I’ve been there, actually.

Lisa: Yeah, so it just opened to the public two months before I went there in the summer of 2010. And it really was the site itself that made me have the idea for this piece because it’s so incredible and you can hear dogs bark from 400 meters away.

Arturo: It’s very flat and sound just goes right across, yeah. And it’s in Berlin, too, so you have a huge community that you can draw upon that are local, and it’s also a new place. I mean, it’s a repurposed place that had one function and now it has sort of a new function. And to draw attention to that is a great way to bring community together and take another look at the architecture of the space. Not just the building itself but like the layout of a runway. It’s pretty intense. It’s not like a highway, where you have geography or topography that dictates where a road is going to go, or you blast through a mountain to make a road. It’s actually like: you level the earth.

Lisa: And not only do you level it, but you strengthen the ground underneath it so that it can handle this, you know, this seven-ton plane landing every seven minutes for 11 months.

Arturo: Well, also because we’re working with airports, it’s in the name: port, portal. There’s a portal, in some ways, an oracle, that we’re looking to hear the voice of the location, which is a landing strip, where things come down, things go up, there’s so many aspects to it. It’s a place you look down on, it’s a place you wait for things, you look up. There’s the poetics of the space itself that I try to keep in the back of my head. There’s all this history that you either go with or go against or ignore.

Lisa: Or you let it buoy you up. You problematize it. Yeah. But I really would like to talk to you about community and creating community in these historic spaces because as you probably know my project is also going to San Francisco. And Crissy Field has already been repurposed. In other words, they raised all this money and they spent ten years—mostly private family foundations—and they have now changed it into a park, which means there aren’t runways anymore but there used to be.

Arturo: Right. It’s grassy. I saw it on your blog.

Lisa: See? Yeah. And when my piece goes up there, totally coincidentally, there are going to be huge Di Suvero sculptures. They’re not there now, but they’re gonna be there. So, like it or not, I am now collaborating with Di Suvero sculptures. There are a lot of differences between these two locations. Those performances are in October, so I have a little more time there, but it’s also ramping up.

Arturo: Well, you’re working in two different nations, you’re working in two different cities, two different sets of communities. Just from the work that I’m doing, working with one city—half as much in a sense—it’s already feeling like maybe I need more time.

Lisa: I went in here with exactly what you just said in mind. Like, ah, community! There are all these people in Berlin, and all this creative energy. Over the last two years, I’ve been recruiting musicians and stuff here and now I have around 180 people sort of locked in in Berlin, although I don’t really ever know what “locked in” means here, because people just change their plans, and Berlin is a very changeable environment, a very changeable city, and groups that were at the center of the project, who seemed really excited, now they’re like “oh no, we don’t really feel like it.” Whereas in San Francisco, I recruited for around two weeks and I got almost a thousand people.

Arturo: That’s amazing.

Lisa: And not a single group has wavered. And they’re supposed to be groovy Northern Californians. I mean, there are some boring reasons for this, like the fact that I grew up in San Francisco, so I’m a local girl.

Arturo: Right, that also improves your chances in a sense, too. I mean, people like it when you have a personal investment in a location. If you’re working on a location-based project, personal investment sort of is like 50% of getting other people involved, because you find everyone else that’s also personally invested and you can talk to them on a certain level, you know?

Lisa: Don’t you find that sad, to have this biographical thing? I mean, we’re artists, right? I’m personally invested in any site I fall in love with. Like, why should it matter that I went to high school there? That’s my own emotional enjoyment factor, but that’s not me as an artist. That biographical stuff I think is kind of boring.

Arturo: I agree. But also, projects of this scale, you kinda have to pull out all the stops and you have to use every possible angle in order to make the project happen, because there are so many things working against you: there’s municipalities, there’s just time and space because you’ve got a large location you’re working with—me too—and then there’s just the logistics. The logistics of it can take over the artwork so quickly.

Lisa: And how many bodies are you actually hoping to pull together there total?

Arturo: 3,000 people. So, just being able to call on the mutual history and the common situation that we’re all living in this city and that we all have something in common is, I think, one of the strengths of the project. Even though it’s like a personal history thing for me, that’s one access point to drawing together that many people. Then there’s plenty of other access points, too. There’s a lot of people who are interested in playing large games. Then the aircraft aspect, that’s a whole different set of people, because it’s not just an aircraft that is going to interest people interested in aviation, but it’s also human-power, hybrid-electric, so there’s environmental and sustainable aspects; there’s fitness aspects to it; there’s the human-powered DIY community that will have an interest in it. So the whole project, to me, is coordinating communities. And the fact that I’m heading it up is irrelevant. I want the project to happen, I want all these people to meet, I want the ideas to happen and the excitement around this event and this sort of social art object… I’m not trying to micromanage or any of that stuff, which is exactly the opposite of what I normally make. Normally, I’m a solo performing artist that’s working in indoor space, most of the time and people come to see. In this case, there will be people there who are gonna watch because it’s a park and I’m not going to refuse anybody, similar to your project, but everybody who’s going to come is going to be a participant. I’m not going to advertise it as a performance, I’m going to advertise it as a participatory event.

Arturo Vidich, excerpt from The Daedalus Effect and Other Dilemmas

Lisa: Yeah, it’s interesting. One of the things that I’m most excited about now is that SoundCloud has partnered with us here. Anybody anywhere in the world, if they can get here for the weekend of the event, then they can upload an audition to the SoundCloud and can be part of it, and you just come to one rehearsal that day. So what that means on the back end, of course, as you can imagine, is that the whole thing has to be supported by this skeletal structure. Not even skeletal, like a muscular skeletal structure.

Arturo: You’re much further along on your project that I am. I’m still in like the drawing, planning phases right now.

Lisa: But one of the things I love about hearing you talk is that you sound like somebody who’s at the beginning of a project.

Arturo: I am very much so, yes.

Lisa: You have great energy. You’re like “More! More!” And I’m like, man, this is all I see in Berlin, is this tiny little Airbnb apartment. I am creating performance materials 14 hours a day right now. If I go outside, which is hard on my eyes because I’m, like, so tired…you know what it’s like. So, I listen to you talk and I think, “oh, I remember those days when I…” I feel like I’m your mom, or something. Like, “when I was your age…” I remember feeling so excited about all the different communities, like “my piece is going to bring together this community and that community.” And there’s this reaching out part of the artistic process that I actually miss. But now, hearing you talk, I think “oh god, how exhausting!”

Arturo: I’m already exhausted. It’s piggybacking on the whole application process for Creative Capital. I just received, in January, the Performing Arts grant. It just blows my mind to be included in such a stellar cast of artists, and just to understand the depth of what it means to receive a Creative Capital grant. It’s a long process, as you remember; it’s like nine/ten months from when you’re thinking of what to apply with all the way to hearing back. So, during that time, I wasn’t just sitting around waiting for the project, to hear about whether I got the grant. I was developing the project, thinking “if I don’t get the grant, at what point do I say I cannot do this project?” And there is no point, because all you have to do is rejigger it a little bit to make it so that some aspect of it is still possible.

Lisa: Well, you’re talking to somebody who has rejiggered. This is something I’m not at all shy to talk about, because what happened with this—and I spoke to Ruby Lerner at Creative Capital about this, too—what happened with this project was that we did some crowdfunding and looking for funding in the States. But we applied for 11 grants in Germany. We got zero of them. ZERO of them. So, the version that I’m going to be slapping together, with all kinds of love and rigor, is really, I would say, almost down to a tenth the size—in terms of budget. It’s amazing how grassroots you can suddenly get if you have to be.

Arturo: I know, I have several budgets that I’ve laid out: the pie in the sky and the bare minimum. I’m flexible, but I’m also hopeful. I mean, this is the beginning stages of any project. You’ve got your budget, all the grants say “pending,” all the foundations—nobody’s gotten back to you yet, whatever, but just being able to divide up the project and be plastic-minded about it, and not have to feel like everything has to go 100% or you’re not going to be able to do any of it…

Lisa: That is really tricky. And this SoundCloud thing is great but people have to audition. When you involve so many people you can’t necessarily dictate the motivations of all these individual people. And some of them really want to but they play an instrument you can’t hear on the field! How do you find a way to be flexible when there’s no electricity out there?

Arturo: Battery-operated amp!

Lisa: Battery-operated amps, we’re using those in San Francisco, but here there’s not the budget for them. I mean, if there was nothing in the budget, I’d pay the filmmaker. That’s what I’ve learned from Creative Capital. No matter what happens out there, even if I lay a big ol’ egg, I want it to be captured. And this filmmaker has actually gotten really interested in the aspects of the problems we’ve had here raising money, and the cultural thing, too. He wants to make a documentary film of his own about the process of getting this project off the ground in these two cities.

Lisa Bielawa, excerpt from Creative Capital-supported project Chance Encounter

Arturo: Another question: because I’m working in the same exact way—right now I’m looking for a production team and filmmakers who want to turn this into a video documentary, sort of a meta-project that can function on its own. Maybe it’s a sensitive thing, but I still would love to hear how you have a relationship with those people?

Lisa: There have been some frustrations. Some of these relationships I was able to forge, and some of them I wasn’t. I learned German in order to forge relationships.

Arturo: You have a good accent, too.

Lisa: Thank you! Yeah, I learned German in order to come here and do this. I mean, it’s not great, but I can communicate. I can run a rehearsal in German.

Arturo: Over the last few years, are you the one that’s primarily been the grant-writer and fundraising captain? Or have you hired somebody?

Lisa: Yes, although this time I did hire—obviously I couldn’t write grants in German. I started out with a translator and then the translator’s cousin became my production manager, because she’s a corporate event manager for the Berlinale film festival, so she has experience in that area and she wanted to get involved with more artistic things. In fact, the woman who was the translator I met because she’s married to somebody who was a Creative Capital grantee the same year I was. It was a relationship that came through Creative Capital.

I did hire a grant-writer in San Francisco. The problem is that this project is so big that, even though I can do many aspects of it, I really shouldn’t be doing all of it. And one of the things I’ve learned in this project is I’m used to things working… I’m a musician. You hire a string quartet, they learn your string quartet. Someone’s not cutting it, you get someone else who can cut it. Everyone that gets hired, they do exactly their job and they do it well. That’s not like the real world. My advice would be: if you want people to be invested, like you do, be really honest about money all the time. Keep bringing it up, not ad nauseum but don’t let too much time go by without bringing up the subject of money. And the other piece of advice that I have is: let the job title and job description fulfill itself over the course of the early part of the relationship that you’re making with someone. Then if there’s a hole, something that nobody’s doing—“oh, shit, nobody’s doing publicity,” or whatever—then you have to go find somebody to do that thing, whatever’s left over.

Arturo: We’re working with an aeronautical engineer. Obviously. My collaborator Daniel Wendlek and I, neither of us have ever built an airplane. Daniel understands pedal mechanics and a lot of the aspects associated with the bicycling of a vehicle or of an instrument. I’m a choreographer, improvisational dancer, artist; I make things, objects and videos. So there were plenty of holes to fill when we started to talk about this project.

Lisa: What I have needed to learn to do is to give people space to imagine themselves in the project. To make it their own they have to have their own imagination experiment, alone. After talking to you, before they make it their own. It has to take root inside them. And it’s tough because of course I want them to just dive in whole-hog. But I can’t take it personally if somebody actually wants to get married instead.

Arturo: I feel like we’ve been talking a lot of logistics, which in some ways is 90% of our projects. 10% artistry.

Lisa: But you know what Christo says about that, though. He says that if you feel like all the logistics take over and then you can never actually get to the art, then you’re actually in the wrong field. He said, “you have to feel like the town meetings are the art.”

Arturo: Because if the community rejects it, you can’t do it. So it’s this negotiation, and I feel like I’m becoming a really good negotiator just by doing this. I wanted to talk to you about one-day events and all the investment putting into one day.

Lisa: You’re talking about sustainability, which is something that I’ve gotten very articulate about because funders need to talk about it. The fact that it’s an event, a lot of foundations are like, “we don’t fund events; we fund organizations.” This project, one of the ways in which it’s sustainable is it happens and it brings people together and it catalyzes new relationships. Marc Kasky is my director for civic engagement because he’s not really an events person. He’s the one that people entrust former military lands to when they want to change it into cultural space. So this is sort of what he does, and he’s never been involved in arts. But he’s really interested in this project because he likes the way that it might actually catalyze new awareness, new partnerships. Maybe other cities will see that through art-making they can do place-making. And that’s something that’s really in the air right now.

Arturo: And artists can see that what they’re doing can go beyond the art context. It doesn’t always have to be in a gallery or a designated area for art. Art can be totally out in the world and involve people that are not artists who could give two shits about the dialogue, but it’s still part of the dialogue.

Lisa: That’s exactly right. As tired as I am right now, this work that you see me doing here is really joyful for me. I really like it. I wake up and I look forward to it. Still, even though I’m down to the wire, because of this very thing we’re talking about—the mechanics, the intellectual challenge of making the mechanics work out—I can’t get enough of that, I’m totally addicted to it.

Lisa Bielawa presents the first performance in her Airfield Broadcasts series at Tempelhof Field in Berlin May 10-12. Arturo Vidich is holding two Tag game tests on May 19 and June 16. If you are interested in attending or want more info, email [email protected].