Jane McFadden On Her New Book About Walter de Maria

Jane McFadden won a Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Arts Writers Grant in 2011 for a book on Walter De Maria. Her book, entitled Walter De Maria: Meaningless Work, was recently published by Reaktion Books. Steven Zultanski, Manager of Grants & Services at the Arts Writers Grant Program, spoke to Jane about the new book.

Steven Zultanski: Can you tell us a bit about how you became interested in De Maria, and how this book project came about? When did you start working on it, and what was the process like?

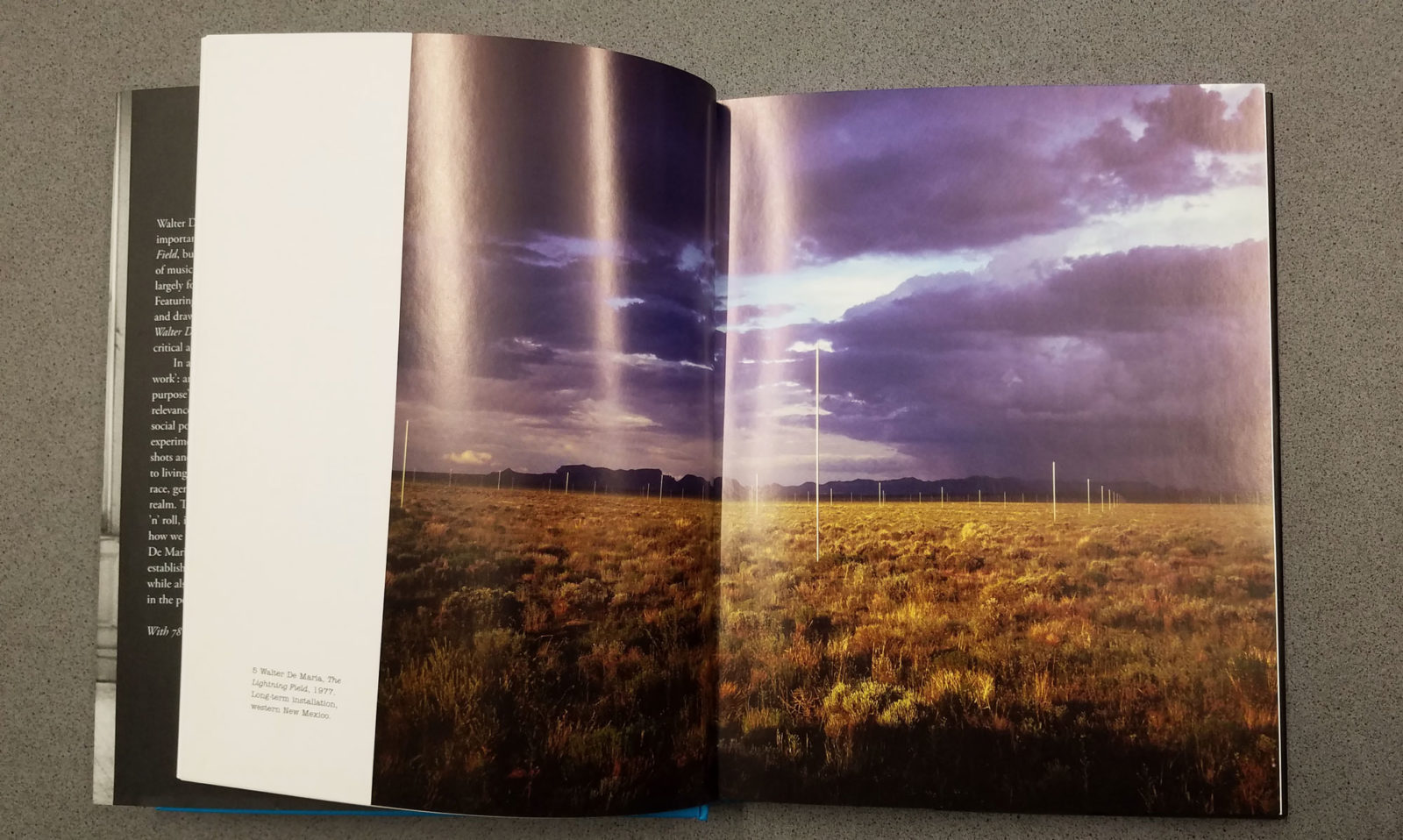

Jane McFadden: This project really began with a first visit to The Lightning Field in New Mexico, which took place on a road trip between graduate school in Austin, TX, and a summer working as a wilderness ranger in Utah. That trip was also my first significant western road trip, that quintessential American journey, distinct from but related to the sojourns that informed so many artists of De Maria’s generation. The Lightning Field marked an in-between space for me, literally and figuratively, between the intellectual research of a student and the physical knowledge of a ranger, between institutions of culture and the culture of nature, between intense mental focus and a more meditative kind of experience. From there I began to question where and how we experience art in general. Sure, New Mexico was an extreme example, but a score of La Monte Young was extreme as well; and I realized that there was a lot of work to be done complicating our understanding of this history in relationship to changing forms of media in general.

Walter de Maria, self-portrait

The book project began forming almost a decade later and was part of the process of being a young professor, raising a family. The year of work funded by the Arts Writers grant was an unbelievable gift. The fact that childcare could be a part of my budget seemed revolutionary, radical even. That year I sketched the book out in almost complete form, but it took a while to finish. The problem with writing more slowly is that you keep learning and growing, and so the whole project keeps changing. Working on De Maria was even more complicated because there wasn’t a singular intact archive available. Everything had to be dug up and brought out. Archival discoveries can be like treasures in that way. I am particularly grateful to all of my colleagues who shared their own discoveries with me and delighted in the process with me as well.

The idea that a work is “minimalist” or “conceptual,” let alone “land art,” limits how we might understand the theoretical possibilities of art. It is like locating a city on a map but not bothering to visit.

Steven: You talk about De Maria’s work in terms of its “meaninglessness” and resistance to commentary. How do you think this dovetails with his interest in site?

Jane: Site-related works are one example of how the experience of a work might overwhelm interpretation, or meaning. Really, even now, how do we explain what the The Lightning Field might mean? We can’t and I didn’t want to either. It is meaningless in light of its profound possibility. De Maria could not have imagined then the onslaught of information and analysis that we confront in any given hour now (so much meaningless meaning), but he knew Time magazine [in their 1969 article “High Priest of Danger”] was sensational enough to suggest caution and resistance. He wanted a different space of experience, even if it ended up on the printed page.

Steven: You frame De Maria’s practice not in terms of land art or minimalism, but in terms of intermedia or intergenre art. Can you tell us more about these terms? Are they key to how you think of De Maria’s influence and relevance today?

Jane: Intermedia and intergenre were a way to think through certain historical categories as well as certain Modernist theorizations determined by medium. Dick Higgins, via Fluxus, provided “intermedia” as a way to understand emerging event based practices. In turn, Henry Flynt’s intergenre music suggested to me that it was in these slippages between established forms that artists were finding traction. De Maria certainly was.

Scholars have theorized the break down of medium, of course, but the idea that a work is “minimalist” or “conceptual,” let alone “land art,” limits how we might understand the theoretical possibilities of art. It is like locating a city on a map but not bothering to visit.

Steven: At the end of the book you propose reading De Maria’s work as “history sculpture,” suggesting that the work is “not just an abstract formal experience but… a historical one….” Can you say more about how the historical functions in De Maria’s art?

Jane: De Maria had a strong interest in history and I think it is resonant throughout his practice. When he makes a work out of a 1955 Bel Air, that resonance is a bit more literal; and I see that particular late work, which he situated within a retrospective, as a kind of wink to a longstanding interest that can be traced elsewhere, although less visible. De Maria had a tendency to layer historical content and contexts into his work. We have an established understanding of the genre of history painting, of course, but the idea that minimal sculpture would carry and comment upon historical content, rather then merely reflect its historical context, is a bit more startling.

Steven: Where has this book led your research? Did it segue into any future projects?

Jane: One of the projects that came out of the book was on Marcia Hafif, who I started talking to when I was doing research on the PS 1 Rooms exhibition. I wrote a fairly extensive essay on her last year and am still researching her work, particularly, An Extended Grey Scale, 1973, a painting in 106 parts. Unexpectedly it turned out that Marcia had connections to and interest in similar kind of minimal music as De Maria, among many other fascinating elements of her extraordinary career. I am also working on an essay on Chantal Ackerman’s film, Sud, 1999, which certainly relates to questions in the book about site, medium, place, history, and the ways that art and landscape might embody stories and experiences we cannot otherwise adequately access. I imagine that work will continue to develop for years.

Find Jane McFadden’s book, Walter de Maria: Meaningless Work, on Amazon here.