Artist to Artist: Cory Arcangel and Julia Christensen on Media Fluidity and Obsolescence

As part of our “Artist to Artist” interview series, Cory Arcangel (2006 Emerging Fields) and Julia Christensen (2013 Emerging Fields) connected over the phone to discuss DIY projectors, technological obsolescence, source code, and other issues related to their media-based practices. The following is an edited excerpt from their conversation. You can listen online to the full podcast, or subscribe through iTunes.

Julia: Hello! Great to talk to you, Cory! So you’re in Norway right now?

Cory: Yes, I’m in Stavanger, Norway… Are you in Oberlin?

Julia: Yes, I’m in Oberlin, Ohio. It’s winter term here, which is this wonderful break Oberlin gives, so I’m in the studio 9-5 right now, which is really good.

Cory: And what are you working on?

Julia: Well, primarily I’m working this project that is being supported by Creative Capital.

Cory: Aaaahh. At that point they should throw in a Creative Capital audio watermark. CREATIVE CAPITAL. And an airhorn. (Laughs) Cool.

Julia: Sound effects every time we say Creative Capital! (Laughs)

Cory: What year did you get the support from them?

Julia: This year…

Cory: OK! So, it’s new.

Julia: Yeah, it’s new. 2013. And you were in…?

Cory: ’06. And I must say I’m still working on it. Slash, just started.

Julia: Cool.

Cory: Not just started…it turned out to be a more complicated project than I ever imagined. But anyway, tell me more!

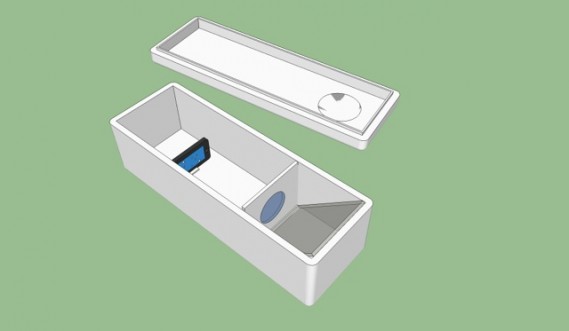

Julia: Well, I was just beginning this project when I saw you in Oberlin the year before last, and it’s also more complicated than I expected in the first place. So this body of work that Creative Capital is supporting is called Project Project. Basically, I’m building functioning video projectors out of trashed electronics that I find and that people give to me, and I’m also making video pieces out of trashed or discarded media that I find or people give to me. Right now, I’m working on two projects under this umbrella. This is a body of work that I feel like will be happening over the next few years. I could tell you about the two projects that I’m working on and maybe that will help articulate what it is that I’m doing.

Cory: Yeah. We have two categories. One is projectors and one is videos. Are the two projects related to those categories?

Julia: Yes, they are, actually!

Cory: Keep going, I’m interested. I’m vaguely aware that it might be possible to make your own projector, but I really don’t know anything more about that.

Julia: Well, the projector project that I’m working on right now is built out of my friends’ old iPhones. When the project began, I was interested in seeing what my friend group had in terms of technology and what they do with it when they’re done with the technology. So, I sent out a big email to a lot of friends and a lot of people responded that they had old iPhones in drawers and closets and that kind of thing. And so I asked them if they would send them to me, and a lot of them did. So, I started to figure out how I could make projectors out of them and—

Cory: Oh whoa, slow down. How many did you get?

Julia: I have nine right now in my studio.

Cory: And what was the leap from having a drawer full of nine phones to making projectors?

Julia: Well, I had been sort of interested in projection and had been playing with projection in a few other projects before I got into this. So, I started to think about how projectors are relevant to a lot of different kinds of media and artwork and stuff, and I didn’t really know how they worked or how they were made, so I started to look into making my own projectors. And then when I had all of these iPhones being sent to me, I was like, “Oh, I wonder how I can focus this light and turn these old iPhones into video projectors.” And then I just started to experiment with lenses and mirrors and things and wound up building these functioning projectors that use the old iPhones as a light source.

Cory: How does a projector work? I have no idea.

Julia: The projectors that I’m making are really simple projectors that kind of use the setup that an old overhead projector used, with lenses and mirrors. So, I have one light source, and that’s the iPhone, and I just direct the light source through a series of lenses and mirrors that enlarge the video and throw it eight or ten feet onto the wall; the projectors that I’ve made out of the iPhones actually project onto the ceiling.

Cory: And the iPhone itself is the only light source, so is it bright? It’s not that bright?

Julia: It’s not that bright.

Cory: How many lumens are we talking here?

Julia: (Laughs) Not that many lumens. They’re pretty dim. And all the projections are iPhone-shaped…

Cory: Oh, that is too funny.

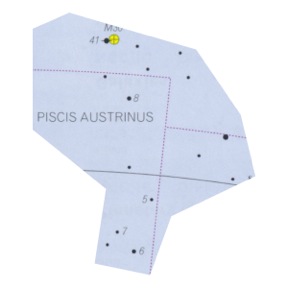

Julia: …so you can see the iPhone-ness in the projection. And the videos that I’m making for the iPhone projectors are of constellations from the night sky. I started doing this research about obsolescence and science and technology and somehow or another wound up on this Wikipedia page about retired constellations. So, it turns out, over the millennia, as astronomers update star maps, they sometimes deem certain constellations to be irrelevant to the study of the night sky, so they leave those constellations off of the next star map. So there’s actually a list of 43 retired constellations that are still up there, hanging out in the sky, but are not used anymore by science—they’re retired.

Cory: That’s so sad.

Julia: Totally! I thought that the retired constellations were a nice poetic parallel to our retired iPhones that are still working and still functioning but are deemed no longer relevant. So, I made videos of these constellations and the iPhone projectors are projecting these constellations onto the sky in the gallery, or the ceiling, I guess.

Cory: Are the videos of the constellations videos of the actual stars in the night sky?

Julia: No, they’re visualizations from maps. I’ve made the videos—they’re animations that I’ve made out of the star maps. I went to—so, here at Oberlin we have a little planetarium. You’re an Oberlin grad, I don’t know if you ever visited it…

Cory: No, I did not even know.

Julia: It’s in this very old building that has a dome on the top of it. There’s telescopes up there and stuff.

Cory: I didn’t even know about the art library until my senior year. I was a total music conservatory student so I had no idea what was going on.

Julia: It’s funny how it’s such a small town and a small campus, and yet a lot of times we don’t know what’s happening on the other side of it.

Cory: Yeah, totally. I bet both of those things help each other. You know? Like in New York, everyone kind of knows everything. (Laughs) Wait, so where were we?

Julia: So, I went to the planetarium to inquire about these constellations and started talking to the planetarium director. He spent a day with me. He’s amazing! He’s a retired high school teacher who took the job of director of this planetarium because he’s an insane expert on everything about the night sky.

Cory: Yeah, people get really into it, right? It’s kind of like trains.

Julia: Yes. Exactly. There’s a culture around this. It’s really interesting. He basically sat with me in the planetarium all day and helped me identify where these constellations are. And I learned that part of the reason that they are retired is because a lot of these constellations and stars you can no longer see from the earth because our light pollution and the illumination of our planet has increased so much—that there are stars that you can’t see anymore that an astronomer hundreds of years ago in northern Germany would have seen.

Cory: So it’s not because there’s so much light in your particular area, that’s just because there’s so much light everywhere on the globe.

Julia: Right.

Cory: Wow. Cool.

Julia: Yeah. Finding them even in the planetarium was difficult because the stars are not even really marked anymore on the map. So, there were five constellations in particular that were named after technological inventions. There’s an electric generator, a print shop, a telescope, a hot air balloon and a sundial. Those five constellations were the ones I most wanted to identify. So, we found them, so I’ve been able to make scans of the map of where they were, or would have been, and that is what I’m using to make these animated video visualizations of the constellations.

Cory: So, in a way, it’s better that the iPhones don’t have a lot of light. Because that just seems like it’s more poetic.

Julia: It is kind of lovely, these sort of faded, faint, iPhone-shaped visualizations of retired constellations.

Cory: Do they look like ghosts?

Julia: Kind of. Yeah, they kind of have a ghostly effect… So that’s Part One of my project, but before I talk about the other part, I want to hear about what you’re working on.

VIDEO: Cory Arcangel & Michael Frumin, Pizza Party, 2004 (demonstration video)

Cory: So the project I got the grant for eight years ago is called The Source. It’s really super-related to all of this. Basically, I’m going through all my old projects and any one of my older projects that has source code to it, I’m basically publishing the source code as a kind of magazine, and the source code is footnoted as well—the footnotes are more artist texty. So, I’m going through one at a time and,over the past 15 years, I have maybe 30 projects that involve some kind of computer source code. I’m trying to publish maybe six a year; that’s pretty ambitious.

Maybe over the next seven or eight years, eventually I will have republished all of my computer source code. And they’re published on this super archival ink and super archival paper—which is supposed to last 300 years, they tell me; it’s super non-acidic. I’ll sell them off my website and they’ll be in stores. They’ll be, I think, $19.95, so they won’t be too expensive. They’ll be an open edition, so I’ll just keep printing them for as long as people want them. And also they will be on the web, too.

Cory Arcangel, “The Source – Pizza Party,” 2013. Zine featuring the source code and interview relating to Arcangel and Michael Frumin’s 2004 software, “Pizza Party.”

Yeah, I mean, I got the Creative Capital award like eight years ago, and I was like, “Oh, this will just take…it seems like it’s pretty easy.” But I didn’t even have a record of what I had made! So, I was like, “Oh, jeez, first I have to figure out what I’ve made?” The whole thing—I actually had to start over. I had to create an archive of my work, and that took years. And I had to find everything again, and get organized, and that took years…. It feels really good because once I make a zine for one of these things, it’s kind of like I’ve washed my hands of the project.

Julia: Do you feel like, once it’s written down on paper, then it’s solidly there for the archive, and for the future?

Cory: Yeah, there is something about quote / unquote “publishing” that it does force you to really check it over. People don’t really do that on the web, and I don’t. So when these are done, that’s it—I will never need to look on my hard drive again. And I kind of knew that because I had published source code over the years and I was always looking at the published version and never the version on my hard drive if I had questions. So it’s kind of a preservation project, it’s kind of an archival project, it’s kind of a paranoia project, like what happens when my hard drives no longer work?

Julia: It’s interesting because it’s also a distribution project in a way…

Cory: Totally, which is also related to paranoia—like, if I can get these around the world, it will always exist somewhere. Distribution as a kind of paranoia.

Julia: I was just thinking about how we use new technology in art and life, but how it’s very fluid with things we don’t think of as big-time technology, like paper… The fluidity between those older innovations, and what is the new technology or innovation at any given time, is interesting.

Listen online to the full conversation (50 Minutes)

Subscribe to Creative Capital podcasts through iTunes